Hugo Pratt was born in Rimini in Italy in 1927, but he grew up in Venice, where his cosmopolitan family lived. His grandparents had French-English and Jewish-Turkish origins. His grandfather was a leading figure of the Fascist party in Venice and his father, Rolando Pratt, decided to move his family to Ethiopia following the colonial venture. As Pratt wrote, “We were imperialist in order to become bourgeois” (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022, p. 42), but the colonial and Fascist dream was shattered by the African experience. A teenage Pratt discovered the violence and absurdity of Italian racism.

At the end of the war, Pratt started working in the emerging Italian comics and illustration sector. He participated in the Venetian “Uragano Comics” group. But his artistic and professional flourishing took place in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he lived for 13 years, working with established comics publishers and with renowned writers, such as Héctor Oesterheld. In 1967, Pratt returned to Venice, where he published La ballata del mare salato (The Ballad of the Salty Sea), in which he introduced the sailor Corto Maltese (Fig. 1), a character who changed Pratt’s life and the history of comics (Pratt, 1967).

Pratt, like Corto, was a romantic adventurer who embraced life and humankind in all its forms and contradictions. Pratt epitomised Terence’s aphorism: “Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto”—“I am human, and I think nothing human is alien to me”. The only thing that Pratt refused was middle-class moral conformism (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022). As Corto stated: “I’m no one to judge, but I only know that I have a genetic aversion for censors and arbitrators [probiviri, Latin in original]. But, above all, those who I despise the most are the redeemers” (Pratt, 1985).

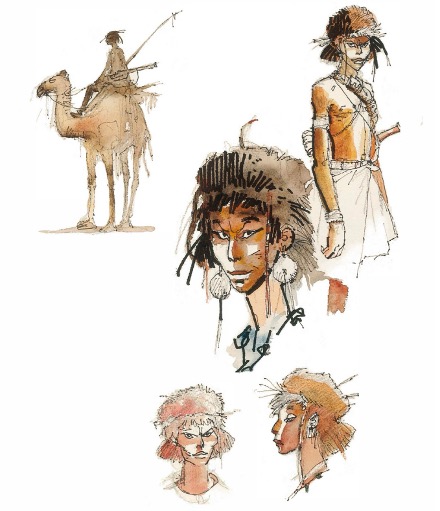

Corto Maltese, as the prototype of the stranger and adventurer, is always helping subalterns, without being patronising. He helps revolutionaries in Ireland, Ethiopia, and New Guinea (Cristante, 2017). The most important example is Cush (Fig. 2), a Black Muslim rebel, who shares in some battles with Corto (Pratt, 1972). Cush is deeply religious and committed to his revolutionary cause, which contrasts with Corto’s eternal wandering. Having said that, Cush is not just Corto Maltese’s sparring partner, but a resolute co-protagonist. Cush had significant success in Africa, where he represented the first positive Black character in comics. Hence, Pratt was invited as an honoured guest by the president Agostinho Neto to liberated Angola, where he gave drawing classes in 1978.

In Pratt’s poetics, no one takes himself/herself too seriously. Pratt touches on crucial questions about life, death, politics, and religion, but there is always a sense of playfulness and mockery. Corto is often defeated in his treasure hunt and love quest, but he does not seem overly concerned, as in the case of the beautiful Chinese character, Shanghai Lil, who betrays Corto, snatching the Russian treasure from him and giving it to the needy (Pratt, 1982). This playfulness and disengagement have been key elements of Pratt’s poetics. In the 1970s, a historical period of social and political engagement, he was accused of being childish and useless. Pratt embraced these charges, taking on the “desire of being useless”, the title of his main interview/biography (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022). But this is just one layer of Pratt’s art and poetics, which, as we have seen, helped question colonialism. Furthermore, the playfulness and disdain for material life opens onto another dimension, “what might be” (Affuso, 2013, p. 152): a metaphysical and esoteric dimension. As Cush says to Corto after saving his life, “Those who play with life, as you do, are foolish… And the fools are sacred to Allah’s eyes” (Pratt, 1972).

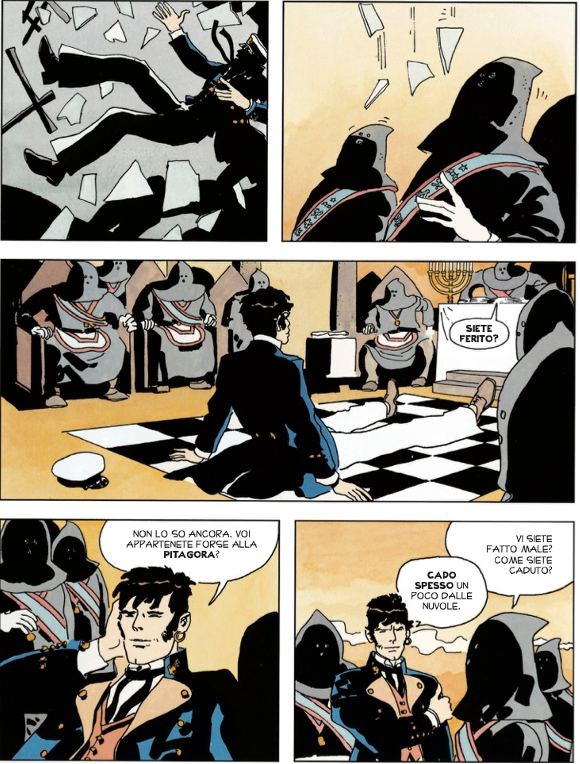

Pratt’s religious education was heterogeneous. On one hand, his parents did not practice Catholicism or Judaism and were openly critical of institutional religions. On the other, Pratt’s father Rolando was a Freemason, a Rosicrucian, and his mother Evelina Genero passed some of her interest in Kabbalah down to her son, an interest that was part of her family background. In Argentina, Pratt experimented with hallucinogenic mushrooms, which helped him “go back to his deep self” (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022, p. 232). In Brazil, he frequented Candomblé syncretic and ecstatic rituals. Back in Venice, in 1976, he became affiliated with the Freemason Hermes Lodge of the Grand Lodge of Italy, one of the A.F.A.M., Ancient Free and Accepted Masons (Prunetti, 2013) depicted in the book Fable of Venice (Pratt, 1977).

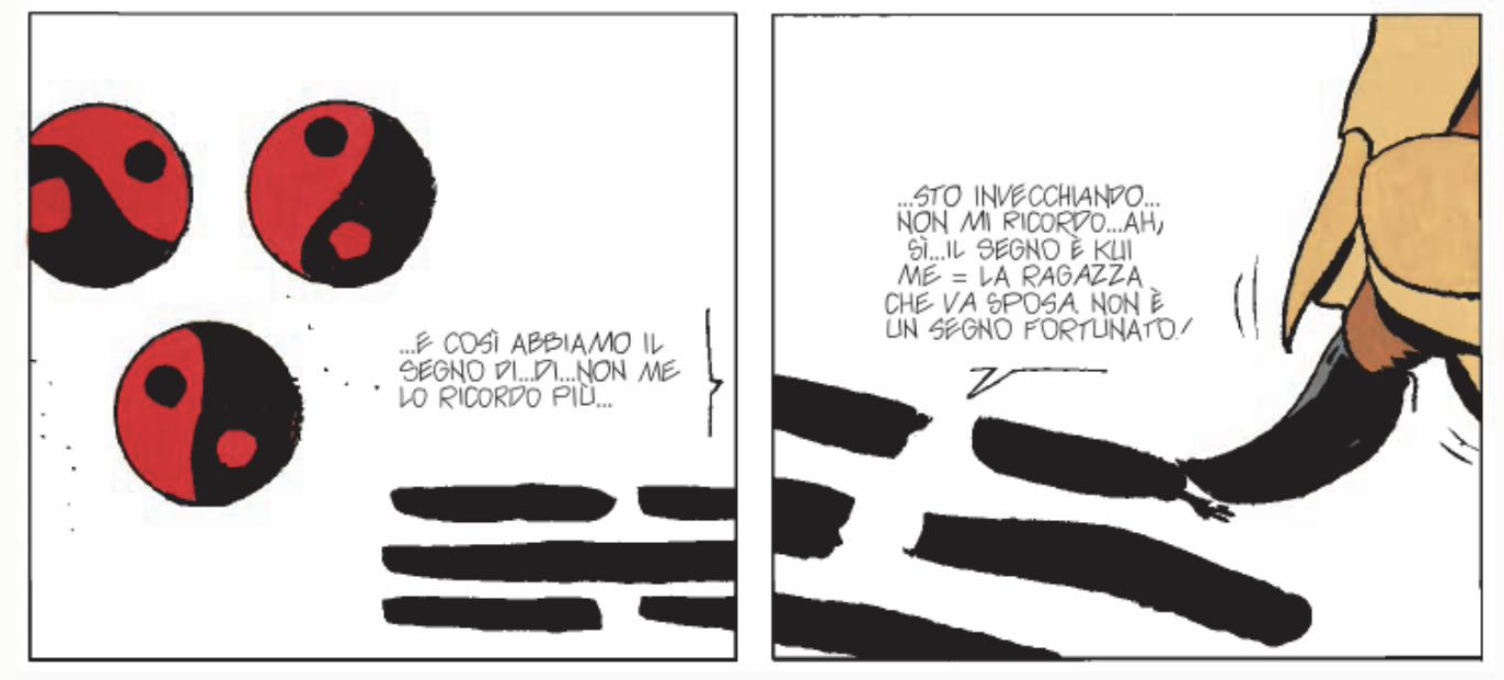

Pratt employed esoteric practices and doctrines throughout his artistic production. Just a few examples are the I-Ching and Shamanism (Pratt, 1982), the Holy Grail (Pratt, 1987), Sufism and Yazidism (Pratt, 1982; 1985), and Christian, Jewish and Islamic esotericisms (Pratt, 1977). Pratt admitted that his work was just a tiny fragment of the esoteric world. With his art, he wished to awaken curiosity in readers, so they could embark on a new (esoteric) journey.

Drawing on different sources, Pratt’s and Corto’s esoteric quests are not bound by religious and cultural frontiers. Like many “spiritual seekers”, Pratt questioned religious institutions, preferring heterodox and marginalised movements, and gave priority to his freedom and judgment (Kokkinen, 2021; Piraino, 2020; Sutcliffe, 2003). Corto mocked and defied deities in Atlantis (Pratt, 1992), such as the devil and death itself (Pratt, 1987), but he also mocked the same Masonic lodge with which Pratt was affiliated (Pratt, 1977). For example, when a Venetian Freemason asks Corto if he is one of them, he replies, “No, no, I hope to be only a free sailor”, and later dismisses any religious commitment, saying: “I don’t believe in dogmas and in flags” (Pratt, 1977).

Pratt’s transcendence remains elusive, incomplete, and out of reach. His religion is “the research. I’m researching the truth, but I know I will never completely reach it” (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022, p. 255). In the comics universe, Corto explains to the pious Muslim Cush that he is not an infidel, but belongs to the Cainites, a religious movement which is still looking for the lost paradise. Similarly, another character, Robinson, is condemned by the shaman-demon Shamael to pursue “the quest of the unattainable”(Pratt, 1979).

In Pratt’s interviews and artworks, we can find several spiritual and esoteric ideas. Pratt believed that reality has a clear, decodable side, but also a hidden world (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022, p. 224). Furthermore, he considered human life to be connected to the universe: “My life began well before my birth, and, I think, will continue without me for a very long time” (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022, p. 171). According to Pratt, all his different spiritual experiences, which could be considered irreconcilable, are characterised by “l’inquiétude”, or unsettledness (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022, p. 237). Hence, Pratt never described (nor probably achieved) a coherent religious doctrine, a cosmology, or absolute knowledge; his, in fact, was an “unsettled knowledge”.

Pratt’s esoteric quest is both transcendent and immanent. His esoteric practices were aimed at “living better to live better with others” (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022, p. 237), which implies that spirituality and esotericism are not reduced to the realm of navel-gazing individualism—they concern humankind as a whole. For example, when an interviewer asked Pratt about the existence of God, he replied:

“For me it is taking the problem upside down. I do not wonder about God, but about men. Hence my interest in myths, through which men try to understand, to give meaning to their situation in the universe. My passion for the myths about our origins undoubtedly reflects a metaphysical concern, but one that is expressed through the human being. I do not pose myself the problem of God, but of man, and I believe in Man. I want to call “God” the vital force, the evolutionary principle of the universe, but I could not believe in the god that each of the great monotheistic religions offers us” (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022, p. 254)

What has been said about Pratt’s “unsettled spirituality” can also be grasped in his drawings and writing techniques. Pratt’s adventures blur reality with dreams, marvels, and nostalgia (Zanotti, 1996). The clouded overlap between dreams and reality can be found in several publications (Pratt 1972; 1977; 1985; 1987; 1992). Pratt himself wrote, “My opinion is that the real life is a dream” (Pratt and Petitfaux, 2022, p. 21). As Umberto Eco noted, these drawings are indefinite and blurred. Over time (in 29 publications over 24 years), Corto Maltese does not age; he is “angelised”, getting younger and younger (Eco, 1996, p. 19). Furthermore, we can also find a playfulness. Pratt often breaks down the fourth wall, presenting his characters as in a theatre play and questioning their existence. Corto, for example, at the end of The Fable of Venice, says, “It’s better not to investigate too much on reality, I might discover that I’m made of the same material of dreams”(Pratt, 1977).

This article is an extract of the following publication Piraino, F. (2023). Spirituality and Comics in Hugo Pratt, Alan Moore, and David B.: Esotericism as “Unsettled Knowledge”. Mediascapes Journal, 22(2), 52–77.